The first time I had to scan a QR code to set up a new device, I didn’t even realise there was a QR code on the device. The instructions were tiny, the code was tucked off to one side and the screen reader didn’t mention it at all. I stood there waving my phone around like I was trying to catch a butterfly, listening to nothing but silence from the camera and hoping I was pointing in vaguely the right direction. The setup failed. The device timed out. And I was left thinking about how something meant to make onboarding easier had become a barrier I couldn’t get past.

That moment captures the real issue with QR codes. They’re useful and increasingly unavoidable, but they’re often designed with a narrow picture of the user in mind. When QR codes are built accessibly, they are brilliant shortcuts. When they’re not, they quietly exclude people.

What QR Codes Are Supposed To Do

QR codes are meant to simplify tasks. They save people from typing long URLs. They connect printed information with digital content. They let you jump straight into a setup guide or sign in to a secure session with one action. Most phones can scan them directly from the camera app, which makes the whole process feel almost effortless.

But accessibility breaks down when the design assumes everyone can see the screen clearly, read instructions quickly or physically hold and aim a phone without difficulty. That’s where things fall apart for blind users, low-vision users, people with cognitive disabilities and people with limited motor control.

Where QR Codes Commonly Fail

Lack of clear and accurate instructions

Many QR code flows simply place the code on screen and expect the user to know what to do. Sometimes you’re expected to use the camera. Other times you must use a dedicated authentication app. Without guidance, users guess.

Instructions need to be clear, specific and easy to follow.

Time limits that work against real users

Thirty-second QR code timers are incredibly common. That makes sense for a sighted developer in a controlled environment. It does not reflect real use.

Screen reader users must navigate instructions before they can even attempt to scan. Some users need extra time to position their phone. Others might be reading the steps slowly due to dyslexia or ADHD.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) requires timers to be extendable by at least ten times and to warn users before they expire. A three to five minute timer with a clear warning and a simple Extend button is far more realistic.

The struggle to physically locate the QR code

You cannot scan what you cannot find. A QR code placed in an unexpected position, partially clipped by zoom or pushed off-screen by scrolling becomes impossible to identify. Magnifier users are especially prone to only seeing part of the code.

This is not a user error. It is a layout problem.

Assistive tech creates predictable challenges

Some examples I’ve run into or seen other users face:

The QR code is printed on the bottom of an item, or under a flap.

The mouse pointer sits directly over the QR code.

Screen curtain is active, so the camera feed is black.

Window size hides part of the code.

The phone is mounted on a wheelchair, so repositioning is not possible.

Magnification settings clip the QR code edges.

These are not rare conditions. They are real-life contexts designers must plan for.

When scanning is simply not possible

Some people cannot lift a phone or cannot physically align a camera with a display. Others may use switch control or external input devices that make aiming a camera impractical.

A QR-only sign-in or setup path is never acceptable.

Designing QR Codes That Work for Everyone

Here are the practical, actionable steps that make QR codes accessible.

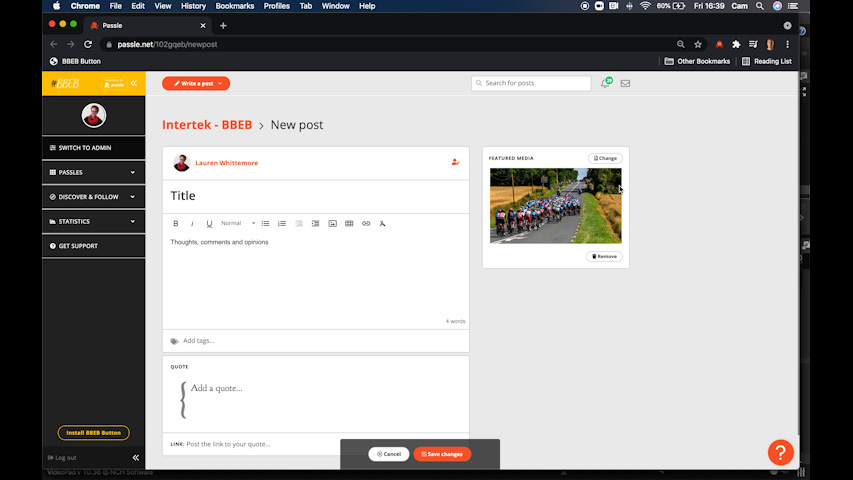

Provide clear, step-by-step instructions

If scanning requires a specific app, say so. If the user must follow a sequence, describe it. Include the destination URL as plain text so users can type it manually when scanning isn’t possible.

Clarity is one of the simplest and most impactful accessibility improvements.

Always centre the QR code

Blind and low-vision users usually begin exploring screens from the centre. Centring the QR code makes it predictable and easier to locate.

Keep the QR code visible at all times

Make the QR code sticky so it stays on screen even when the user scrolls. This prevents accidental disappearance during navigation. If scanning is the primary action, it is reasonable for it to overlap other content temporarily.

If a printed QR code, ensure it has prominent location, is large enough to be scanned easily. Using embossing to provide a tacticle marker for where the QR code is can help blind and low vision users find it.

Allow the QR code to open in full screen

A click, tap or keyboard activation should open a clean full-screen version of the QR code. This eliminates layout issues caused by zoom, window size or magnifier use.

Add screen reader-specific instructions

Visually hidden instructions can explain things like:

hold the phone an arm’s length from the display

disable screen curtain if scanning fails

maximise the browser window

open the QR code in full screen

use an alternate sign-in option if scanning is difficult

These instructions should sit under their own heading so screen reader users can find them quickly.

Hide the mouse pointer if it blocks the code

Auto hiding the pointer after a few seconds (like YouTube does) prevents it from obstructing the QR code. This is a small detail that can fix an otherwise unscannable situation.

Extend time limits

Use longer timers and offer an accessible way to extend them. Keep the warning message short and direct. Something like “30 seconds left. Press Extend to continue.” is enough.

Provide alternative authentication methods

People must be able to complete the task without scanning. Options include:

username and password with two factor authentication

a magic link

a passkey

confirmation via an authenticated device

Choice is the foundation of inclusion.

This Is Why It Matters

QR codes are becoming a standard interaction pattern across services and devices. The design decisions made today will affect millions of people tomorrow. Accessibility is not about fixing edge cases. It is about acknowledging the full range of people who use the web and giving them the tools they need to participate independently.

When QR codes are designed accessibly, they become simple, predictable and smooth to use. When they’re not, they turn into obstacles that disproportionately impact disabled users.

Accessibility in practice is about removing those obstacles before they become someone’s frustrating setup moment.

Takeaway

QR codes can be powerful tools, but only when they are designed with the realities of human use in mind. Clear instructions, generous timing, predictable placement, assistive tech support and alternative paths turn QR codes from barriers into genuinely helpful shortcuts. Accessible QR code design is not complicated. It is considerate, and it benefits everyone.

Sources

QR codes are still fairly new, and far from everyone knows what they are and how to use them! And even if users know how to scan a QR code with their camera app, that doesn’t always work! For example, two-factor authentication QR codes look exactly like other QR codes but shouldn’t be scanned using the normal scanning app or the built in camera scanner – users might need to use a specific identification app to scan these codes. It’s not alway obvious to users when to use which app or why there’s a difference at all, so instructions are vital!

unknownx500

unknownx500