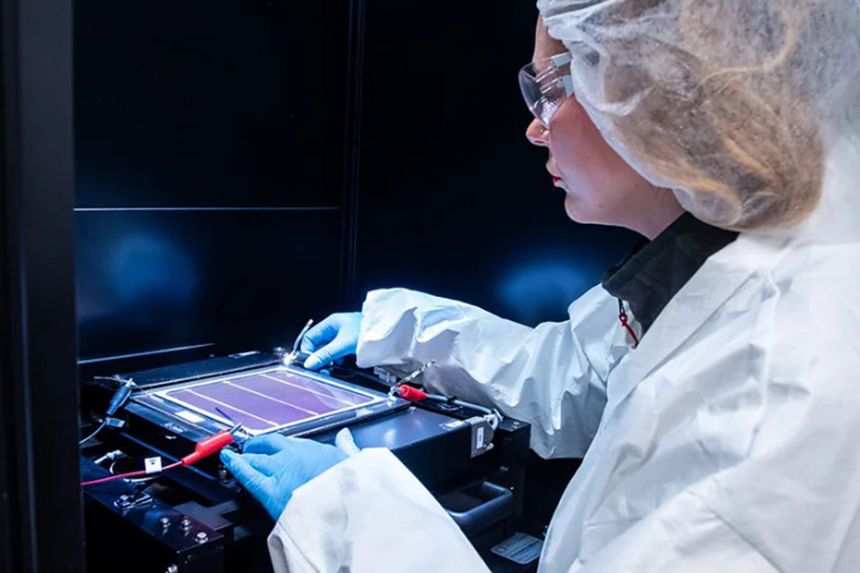

In a laboratory on the outskirts of Oxford, UK, rows of experimental solar photovoltaic (PV) cells await rigorous testing. One researcher uses an electron microscope to inspect the cells for microscopic flaws that could reduce efficiency, while another measures how the cells react to different wavelengths of light.

This lab belongs to Oxford PV—a spin-off from Oxford University and one of several emerging companies worldwide racing to develop what many consider the next major leap in solar technology: tandem perovskite solar cells.

Advocates of this breakthrough say that perovskite-based panels could dramatically and affordably increase the output of solar farms and rooftop installations. They may also outperform traditional silicon panels in specialized applications such as satellites and electric vehicles.

The core concept is simple: combine traditional silicon—the foundation of nearly every PV panel today—with perovskite materials to achieve far higher conversion efficiency. The result is a panel that can capture and convert significantly more sunlight into electricity than silicon alone.

Perovskite was originally identified as a mineral in the Ural Mountains in 1839, but today the term refers to a broad class of synthetically produced materials that share the same crystal structure. These engineered perovskites can be made using widely available elements such as bromine, chlorine, lead, and tin, making them relatively inexpensive to produce.

Some argue advances in perovskite solar cells mean we are on the brink of the next solar energy revolution. But it all depends on how they hold up in the real world.

unknownx500

unknownx500